The 1st July always seems to equally trigger those fresh-start-feels like the 1st January. One being about financial resolutions and the other equal challenge, personal girth. The grand plans are the same. Out with the old lardy habits and in with the new lean machine. There’s nothing quite as refreshing as optimistic new beginnings. Despite Covid’s boot-camp restrictive demands to stay put and like a resolution to make more out of a great deal less, July’s travel aspirations have felt more hopeful. Aided by the landscape being laced with ephemeral but beautiful almond blossom.

This month’s Motorcycle Travel Diary starts in my own backyard with chickens, salad and cake and then heads out to local Barossa Valley gardens, landscapes and places of historical significance. A little further afield, I’ve been loving the twisty ride down and up the Sedan hill over the Barossa ranges to the nearby Murraylands, Riverland and locking on the panniers again for a weekend visit to holidaying friends on the Yorke Peninsula.

Even though I’m now hemmed in by the necessary hard border controls, there’s so many beautiful destinations to rediscover here in South Australia after being away for many years. I hope you enjoy reading about them below too.

After years of looking after chalet and restaurant guests, children, dogs, cat and sharing the care of nearly every type of farm animal you can think of including pigs who deserved names but were destined for culinary adventures on the other side of the kitchen door; my three ISA Brown hens are enjoyable small fry in the barnyard department. Ginger is the smart plucky one who’s about to jump on my shoulder like a pirate’s parrot in this pic above. Babs is the slow rotund one who’s a bit thick but somehow catches the worm first and Bunty is the littlest one who trails behind. The girls are not the prettiest in the collective coop but they’ve so much character, mostly lay an egg each a day and with feeding, watering and egg collecting they make life still feel recognizable. A couple of boiled eggs and fresh radishes pulled from the veg planter box have been a delicious part of many a home-grown lunch plate the last couple of weeks.

And for when those nostalgic moments surface along with more of my little veg garden produce being ready for harvest, I make this much-loved Swiss German salad called Nüsslisalat.

In typical Swiss German efficient style, Nüsslisalat is both the name of this dish and the name of the small salad plant it’s made with. In English, the plant is known as corn salad or lambs lettuce. In French, mâche. In German feldsalat. Despite the confusion, the salad itself is a Swiss Winter staple and one of the many enjoyable legacies of once being married into a Swiss family I continue to enjoy. The individual nüsslisalat plants are trimmed of their root and thoroughly washed before most commonly being tossed with chopped boiled egg and crispy bacon and dressed with a mustard vinaigrette. The above version is a slight variation as I’ve used roasted walnuts and baby capers instead of the bacon and dressed it with a mustard salad cream. Either way, a delicious lunch and memory of times past.

On a bit of a bread making tangent looking for locally grown wheat to kick off another sourdough starter, I found myself back in the Barossa locality of Ebenezer. Along with wine grapes, Ben Schmidt grows hard wheat and barley in this historic Wendish settlement. Prior to collecting some grain from his mother Christine on their family farm in Light Pass, I took a drive out to Ebenezer which is in the Northern part of the Valley. The above ruin was a school built in 1871 and was the only school in Australia to teach the Wendish language. The Wends are Slavic people living in Lusatia in Eastern Germany and have their own distinctive culture and custom. They were also economically and politically repressed and migrated to South Australia around the same time as the German Lutheran congregations from neighboring Silesia who resettled in the Barossa Valley.

Barossans love cake, which I assume is a legacy of its German cultural roots. Coffee and tea in homes is rarely offered unaccompanied by some delicious sweet home-baked treasure. Despite ever tighten winter pants and after milling some of Ben’s barley and wheat with a new sourdough bread making friend, I baked this Salted Honey, Orange and Rosemary Barley Cake. Barley flour has a naturally malt-sweet and nutty flavour that is slightly softer, more nutritious and absorbs more liquid than normal wheat flour. If you’d like to give this cake a go, you can find the recipe on this website under the Baking Sweet section. You can easily substitute the barley flour with wholemeal spelt flour if you’re having trouble finding it.

After hearing a few times over the past couple of months about the Barossa Bushgardens Natural Resource Centre I finally made a visit one late sunny Winter afternoon. This now rambling display of feature gardens was established on a bare paddock bar one 400 year old River Red Gum on the outskirts of Nuriootpa in 2001 by a group of volunteers passionate about protecting and promoting native Barossa flora.

The first plantings were made in rows to create an orchard suitable for producing quantities of easily harvested seed. Original seed came from the three main Barossa ecosystems; higher rainfall ranges to the east; the valley floor with heavy soils and low hills and sandy plains to the northwest of Greenock and southwest to Gawler.

Following a self-guided map and pathway that starts at the Community Centre and Native Plant Nursery, the many garden spaces unfold and include a Sensory Garden, CFS Fire-Wise Garden, Dementia Friendly Garden, Barossa Rare Plants and many other thematic garden spaces promoting conservation, education and the various ways local plant species are critically important for a healthy local natural environment.

Themeda triandra or Kangaroo Grass, along with other native grasses and lilys once covered much of the Barossa, which was generally open woodland. Captain Charles Sturt wrote in his journal “… and the kangaroo grass was so thick the horses had trouble getting through” while he explored this area in the 1840’s. While this patch doesn’t seem as thick as he described, it certainly caught the glowing golden afternoon light.

Bankia’s feature throughout the Bushgardens. According to information from the Australian National Botanic Gardens, there are 173 Banksia species, and all but one occur naturally only in Australia. Banksias were named after Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820 ), who, in 1770, was the first European to collect specimens of these plants. This is Banksia marginata or Silver banksia.

Bark and seed heads of so many trees and plants such as this drooping she-oak trunk and native daisy Vittadinia spp are texture-rich providing extraordinary beauty during the winter months.

As with so many regional areas in Australia, land use and townships in the Barossa Valley have replaced most of the region’s 400+ local plant species bushland. One of the main aims of the Barossa Bushgardens is to encourage the use of native plants to promote biodiversity; making them available to purchase from the nursery along with workshops and events. Aside from the enormous value this offers to the local community, the Bushgardens are equally worth seeking out by visitors no matter the season.

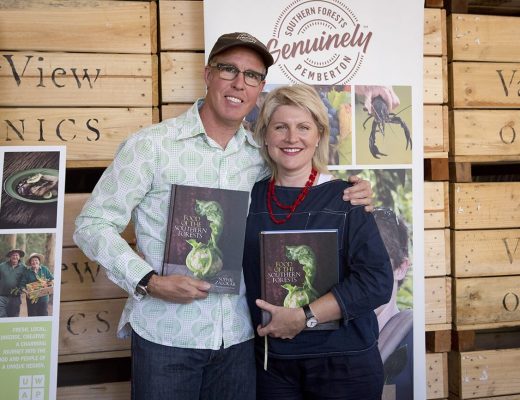

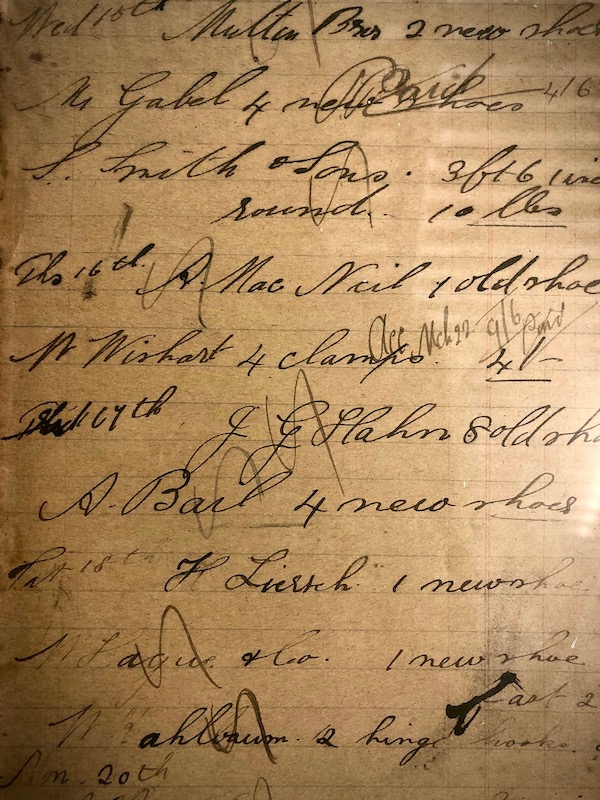

From 1846 to 1980, the once central industrial beating heart of Angaston, the A & H Doddridge forge is now a working museum. Local blacksmiths fire up the forge and hammer out a range of custom metal tools and other items along with offering a display of many of the original tools and equipment used to create wrought iron and steel objects needed in early South Australian life.

After the death of third generation blacksmith Hardy Doddridge in 1981, the shed was to be demolished, however the community banded together to purchase the tools and keep the significant collection of blacksmithing memorabilia together. The now known Angaston Blacksmith Shop & Museum is the oldest main street smithy in rural South Australia to have survived.

One of the many legendary stories of the Doddridges was of Hardy’s sulphur crested cockatoo called Cocky who lived in a cage adjacent to the blacksmith shop. At night Hardy would take him onto a perch in the blacksmith shop. He was fed on thistles, walnuts and bread with warm milk. Cocky was an attraction in Angaston as he learned to talk and would call out ‘aeroplane’ when he heard one overhead and ‘anyone home Mrs Doddridge’ when he heard a knock. He was also known to make indistinct muttering noises as he listened to the congregation chatting outside after a service at the Methodist church across the road. Many residents remember Cocky as they walked past him daily on their way to Angaston Primary School. Cocky lived for 76 years.

Despite this working museum being all about the utility and craft of blacksmithing in time’s past, today’s current necessary Covid-risk protection protocols are clearly in place when you enter. I wonder what Cocky would’ve said to that. The shop is open every Saturday, Sunday and Public Holiday from 1pm till 4pm and at other times by prior arrangement. There is no cost to visit but a donation towards the upkeep is greatly appreciated.

When those beautiful sunny winter days occasionally roll through and I’ve a couple of hours to spare, the call to ride rings loud. The GS models of BMW motorcycles are despite their heft, agile, elegant and powerful stormtroopers. Coming to motorcycles relatively late in life means I’ll never catch up on the years it takes to master the skill of off-road adventure riding but it’s enormous fun trying and the Barossa has some very scenic dirt roads with extraordinary views and roadside botanic beauty.

This view takes in part of the Eden Valley, which lies in the high country of the lower Barossa Valley and was also settled by English and German immigrants in the 1850s. It has its own wine region appellation and within it a small sub-region called High Eden which is where this photo was taken from. The town of Eden Valley had its beginnings like so many localities in this region in the 1850s after land owned by a wealthy English farmer from Gumeracha farmer sold a parcel of land in 1862 to a group of Prussian Lutherans to build a church and school. Two years after the church had been built, the rest of the land was surveyed and subdivided. It is believed the word ‘Eden’ was found carved into a tree and thus Eden Valley got its name.

Collingrove Homestead is situated on the Eden Valley Road approximately 5km south east of Angaston. A re-connection with Jan Angas with whom I worked many years ago, whose husband John is the great great grandson of Collingrove’s founder John Howard Angas; allowed an afternoon visit to this place of significant Barossa history. Conceived as a little piece of England and commenced in 1856, Collingrove was the Angas family home and headquarters for their considerable pastoral interests. This family made substantial contributions to the growth and development of South Australia from its earliest days through political involvement, pastoral endeavor and philanthropic gesture.

The entry to Collingrove is framed by stately red gum eucalyptus trees under which grazing sheep feed and warm themselves in snatches of winter sun. In the early settlement years the ties to England were not only strong in a business, emotional and familial sense but on a very practical level. Most of the day to day items of living were shipped from the Mother country including this sports-car of carriages called the Park Phaeton. It was brought out from England in 1863 by John Howard Angas when he returned with his wife Suzanne (nee Collins) after whom Collingrove was named.

A book published by MacMillian & Co in 1875 by two English ladies called Rosamond and Florence Hill titled What we saw in Australia contains the following passage: “Angaston has a very English appearance. Indeed we might have believed its broad, main street to be the approach to a well-cared for English village, especially when there appeared on the scene a phaeton and pair of ponies – an elegant little equipage, quite fit for Hyde Park – driven by a lady, the squire’s wife as one might suppose.” Standing in front of the coach house looking down the entry roadway you can imagine her returning home and what a gorgeous sight that would’ve been.

When lit, the warmth from the large cast iron range cooker on entry into the kitchen offers not only relief from the icy air but the sense that this once grand homestead was a place of great hospitality. Above the mantelpiece hangs a beautiful naive hand-written and illustrated bible verse: Teach me to do Thy will; for Thou art my God: Thy Spirit is good; lead me into the Land of upight-ness. Psalm. 143, 10. As John pointed out, the spelling mistake in upight-ness was later minutely corrected. Perhaps fortunately with an r not a t. Save for a double clout around the ears.

As with many early settlement homes, they were built and renovated over periods of time as the growing demands of the family, business interests and funds allowed. The bluestone bungalow or villa-styled structure with neo-classical details, bay windows and sweeping crescent entrance is often described in historic accounts as an English oasis bar the corrugated iron roof and verandas that replaced the once slated roof.

Small and large items through the homestead hold the stories of the many lives and interests lived out at Collingrove, including the nations historical period of wool production and horse breeding. Jan also tells of the time women sat in this bay windowed space stitching with no doubt conversation aided by many pots of freshly brewed tea.

Walking around the grounds revealed a small separate cellar that appears, given the remaining equipment for dairy product production to be utilized predominately for this much loved part of a typical English diet. A significant challenge during the roasting Australian summer months.

An early clothes mangle sits retired after no doubt many years of heavy duty service. Prior to being mechanized, they were pretty lethal contraptions and required the strength of some serious house-maid-muscle. From some desktop research on mangles, the recollections of Florence Clarke published on 1900s.org.uk: “When my brothers and I came home from school for our mid-day meal, mangling was still in progress. A lot of energy was needed for it, and I had to help by holding the sheets as straight as I could while my mother turned the handle of the mangle. It was by no means unusual for children to get their fingers caught in the rollers.” On our walk around Collingrove John also pointed out the sleep-out as the place his father Colin slept as a child. With just fly-wire for walls, it seemed as we both stood there on a brisk afternoon trying to imagine, a rather brutal toughening up during winter for perhaps the equally brutal years of boarding school that lay ahead. In the early 1900’s a method considered one of parental duty; now considered deprivation. Past privilege when you take a closer look didn’t always mean comfort and luxury.

The design and location of the above Shadehouse was based upon an earlier shadehouse which was in the garden from C.1890 – C.1950. It was funded and constructed as part of a bicentennial program of the Australian Council of National Trusts and officially opened on Sunday 20th November 1988. In doing the now far too many numbers, my 21st birthday which was a few days prior and celebrated here must’ve been a pre-opening soft-launch event. Weirdly yet another circle-ride moment this time in the Barossa seems to be offering at the moment.

The above portrait is of George Fife Angas. He sent his second son John Howard Angas (JHA) from England to South Australia at the age of 19 after he became increasingly worried about the agents he’d entrusted to handle his colonial interests. Historical accounts and passed on family recollections as told by John and Jan describe JHA as a kind, philanthropic man with an endearing nature who not only turned his father’s perilous financial situation around but donated significantly to South Australian charities. JHA loved his dogs and horses and as was his more serious but partisan father, a social class-dissenter not interested in climbing the upper echelons of English social hierarchy.

The National Trust as an organisation responsible for the care and preservation of Australia’s places of historical significance has also gone through its own evolution. The above copper bath was not part of the life of Collingrove during the time the Angas family lived here but was installed as a museum-like example of mid 19th century living. Whereas the hunting trophies on the passage walls, although in today’s cultural and legal context considered a crime, were authentically part of the cultural life the Angas family lived during the early settlement years.

After the deaths of JHA and his wife Suzanne, their grandson Ronald Fife Angas inherited the property and the home. He moved in with his wife, Monica when he returned from World War I in 1918. Ronald bequeathed Collingrove Homestead to the National Trust of South Australia in 1976. The beautiful oaks and elms with their deep English roots in the Australian soil of Collingrove Homestead share the same heritage as those who planted them. They too live alongside the native Australian gums that preceded them: also holding their own colonial period stories and the ancient ones from millenia before. Today this estate’s now caretakers are wanting with inclusive openness to again share this home and land, engaging with this region’s first people, their stories and the community at large, returning to Collingrove’s once philanthropic heart.

At just under an hour’s ride, the Mannum Waterfalls was a perfect half-day trip from the Barossa into the Murraylands region to take in a spot I’d never visited as a kid. As with so many beautiful locations sign-posted with the easily-missed smallest of signs, they didn’t disappoint. Except this location’s beauty on the day I visited was more about the rock formations than the water which less and less cascades down into full roaring falls.

Admittedly, with a short time frame and wearing around 10kg of extra winter riding gear I didn’t venture the whole scenic 3km return walking trail along Reedy Creek between the Upper and Lower Car parks. However it was enough to take in and enjoy this lovely spot 10km south west of Mannum.

Further on into the Riverland region is the town of Waikerie, which was built around the once mighty Murray River. Reminding me a little of Carnarvon in WA in terms of its volume of primary production, broad acre farms, vineyards and citrus groves covering large areas of agricultural development and sending thousands of tonnes of fresh produce to Australian and overseas markets.

Despite not being previously drawn to much of the art that now covers silos and water towers around Australia, I decided to take a ride to Waikerie and was surprisingly rewarded beyond their sheer scale. These non-working silos have been painted by artists Jimmy DVate from Melbourne and Garry Duncan from Kanmantoo, SA. Jimmy DVate’s silo features local native flora and fauna, including a giant Yabby, the endangered Regent Parrot, Murray Hardyhead and the Spiny Daisy. The other silo painted by Garry Duncan has a semi-abstract river landscape with local, native river creatures including assorted birds, frogs, fish, turtles and the Rainmoth, which is where the town of Waikerie gets its name. The Australian Silo Art project began in Northam Western Australia in 2015. There are currently 36 silos in the Australian Silo Art Trail with many more planned. This movement has given many struggling Australian regional communities purpose and provided positive engagement within and a new destination tourism attraction. The morning I visited coincided with the local Men’s Shed meeting there to discuss the native gardens planned for the river side of the silos. Chatting with one of the very friendly chaps he explained that along with beautifying the now greatly-visited location, the garden will be dedicated to families who’ve lost loved ones to suicide along with those struggling with this increasing mental health issue in regional Australia.

The 130 million year old Murray River that Waikerie was built on flows more than 2500 kilometres from the Snowy Mountains in New South Wales, through the Riverland and onto the Lakes and Coorong in South Australia. Like so many of our natural resources the demands and detriments on this mighty river to support so much life and trade outweigh its natural capacity. Along with the mental health struggles of regional communities I’d just spoken about with a Waikerie local, these reflective thoughts seemed somewhat mirrored back in the river’s ripples as I rested before riding back over the plains and through the ranges to my little Angaston cottage.

On a much more rousing note, the Barossa Regional Gallery in the Tanunda Soldiers Memorial Hall finally reopened after the Covid shut down, so I went to not only take in the current exhibition but take another look at the Hill & Son Grand Organ. This extraordinary instrument had its beginnings in London built for the Adelaide Town Hall which was opened in 1877. It was enlarged in 1885, altered and rebuilt in 1970, removed in 1989 and placed in storage with its fate uncertain. The Organ Historical Trust of Australia were given possession on condition the organ be restored and located in South Australia. Negotiations with the Tanunda Council at the time brought it to its new home at the Tanunda Soldiers Memorial Hall and the mammoth task of restoration began; taking 15 years to complete.

This project represented the most extensive and accurate restoration of a late 19th Century English concert organ yet carried out anywhere in the world. Unfortunately due to Covid all future concerts have been cancelled but tours on a Wednesday morning are now offered. I hope they will resume in the near future; particularly the previously planned concert of Handel’s Messiah.

July finished with an opportunity to visit holiday friends in Foul Bay at the bottom of the York Peninsula. I’d already been feeling the need to be back by the ocean for some weeks. Along with having lived in the port city of Fremantle Western Australia for many years, hundreds of kilometres of my motorcycle travels prior to Covid were along the Southern and Eastern coastlines of Australia. The salty sea air and the rhythmic sound of the ocean feels internally liberating. After 4 months of being in the Valley, this was a kind, timely and generous invitation I gratefully accepted.

An early morning rise and short walk offered a view across to Kangaroo Island from the high, vegetated and rocky coastal edge. Set on 150 acres located 26 km from Marion Bay the isolation itself was a luxury given how many areas of coastline near popular tourism destinations have now become populated.

Our day began with taking the dogs to nearby Butlers Beach. A wide cuttlefish bone and small-shell strewn beach framed at one end by craggy, seawater and wind eroded cliffs. Watching romping dogs with smiles from ear to ear playing on the sand is nothing short of happy making.

The Yorke Peninsula is shaped similarly to the boot-shape of the Italian Peninsula. 300km from Adelaide, Marion Bay sits at the base of the big-toe end and is the gateway entrance to the Innes National Park. It was originally a gypsum port, but now offers access and protection from rough conditions for fishing and crayfishing boats. The jetty and adjacent boat ramp also offers ocean access to recreational anglers and seasonal holiday crowds.

Completed in 1882, the Corny Point lighthouse was originally built to offer protection from the submerged reefs to the grain ships servicing Port Victoria, Moonta Bay and Wallaroo in the Spencer Gulf. The light was manned for 37 years during which the logs were filled with stories of drownings, child death, earth tremors, damage by gale force winds and the record of a school of salmon so large that it took the whole day to round the point to enter the Gulf. The most famous of all the keepers of the light was Captain Webling. On the 30th June 1920, the lighthouse was de-manned and the lighthouse keeper, his wife, family and belongings were rowed to the SS Lady Loch for their last voyage from the light.

Red Hot Poker Aloe, the tough winter flowering succulent native to South Africa were happily thriving and scattered through the towns of the lower Yorke Peninsula. The afternoon light made this mass on entry to Point Turton glow like torches.

Winter is the best time to eat oysters so on our way back to Foul Bay we stopped at Pacific Estate Oysters in Stansbury. Ringing ahead, the very hospitable owner Steve Bowley met us at his shed and generously gave us a lesson in oyster type and farming differences, provenance and most importantly opening technique. The above photo is of a Pacific oyster at the top, which originates from Japan and the Angasi oyster at the bottom, which is a native Southern Australian oyster. Steve farms both on his 20 hectare bay lease in Stansbury; the Angasi being distinctly different in growth rate, size and taste. The Pacific is creamy, firm and sweet with iodine flavour and fast growing by comparison with the Angasi. The Angasi oyster is more challenging having an algal and gamey flavour with a slightly metallic after taste.

The day of meandering along the rocky coast and through fields of just flowering canola ended with a lesson in squid fishing on the Marion Bay jetty from a generous newly retired couple who’d recently relocated to this growing coastal lower Yorke Peninsula spot. Fortunately the lure didn’t snag in the seagrass, which can’t be said for the above thatch of fine webbing in the prickle bush back at Corny Point; albeit quite likely used to its anchoring advantage in the ferocious winds.

Looking south east out over Investigator Strait as we walked the Marion Bay jetty, the gradient light softly slipped into inky darkness. The still sea air filled our lungs fueling the easy banter and laughter of a long and precious friendship making the world in that moment feel a much less wobbly place. A beautiful and memorable weekend.

I set out at the beginning of the year to write these hopefully not too self-indulgent monthly posts as a way of recording my time on the road post-Foragers. I also wanted to stay in touch with you all who I’ve met through Foragers and the many other projects and events both through my work and personal experiences life’s thrown my way. So far it seems many of you have remained open to receiving these installments for which I’m very grateful. Thank you for still being there. And like the wild almond trees in full blossom that dot and line the roads of the Barossa Valley heralding impending seasonal change, staying connected and in a positive state of long-term hope of a post-pandemic world will deliver warmer days.