It’s been a great month. I’ve been back on my bike and have returned to those warm, open and wild places I feel most free in. By circumstance and with time, I’ve learnt that traveling solo invites (or escapes) unexpected conversations, allows observations and experiences into the day I suspect wouldn’t have happened if accompanied and this month’s trip to the South Australian mid-north was no exception.

The first morning in Port Augusta after arriving the afternoon before, somewhat pummeled by a dust storm, I took a walk through the western suburban streets to the Water Tower Lookout. Maybe it speaks more to my own slightly warped sense of humour, but I couldn’t not take a photo of this front yard and its hard-working anti-post box. The first of many moments of laugh-out-loud oddball funny moments on this trip that outback Australia seems to so readily and easily deliver.

The Water Tower was built in 1882 to provide a pressure water supply for the residents of Port Augusta West. From the balcony on a clear day there are panoramic views of Port Augusta, Spencers Gulf, the Flinders Ranges, Baxter Ranges, the salt pans and the Outback landscape to the north.

Unfortunately the dust storm from the day before hadn’t quite settled so this view over Port Augusta, which normally includes the Flinders Ranges, was still pretty hazy. Port Augusta was a central meeting place for many diverse aboriginal groups who met here to trade, exchange knowledge and skills. The town and harbour were established in the mid 1800’s, becoming a port through which wool was shipped to the London sales and supplies delivered for transport to the Western Plain, east through Horrocks Pass, or to the shores of Spencer Gulf and on to the arid north and west. Today it remains a transport hub with freight rail connections to the north, south, east and west of Australia and the location for a long planned for $500 million hybrid renewable energy project.

One of the showcase locations to visit in Port Augusta is The Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden. The Garden was first proposed by John Zwar in 1981 and after many years of planning and planting opened in 1996. It is set across 250 hectares on the shores of the Upper Spencer Gulf featuring plants from Australia’s southern areas with 300mm of rainfall or less. It was established to research, conserve and promote wider appreciation of Australia’s arid zone flora. The Garden is open 7 days a week from 7.30am to sundown with free admission.

The day I visited was a moment in the main flowering season that offered up some stunning specimens on show. Above is Grevillea huegelii, commonly known as comb grevillea. Alongside is a metal sculpture created by Anna Small who with her husband Warren Pickering have various textural, laser cut works throughout the Garden that mirror and blend in with this stunning arid environment.

This very showy Acacia merrallii, commonly known as Merralls Wattle had just passed its blazing golden prime but nonetheless was a beacon for human and winged visitors.

Top of the native flower list to try and catch was the much loved Sturts Desert Pea. As South Australia’s striking official floral emblem, the Sturts Desert Pea was named for early explorer Charles Sturt but was first recorded by William Dampier in 1699, “….a creeping vine that runs along the ground and the blossom like a bean blossom, but much larger and of a deeper red colour looking very beautiful”. With an exceptionally long tap root to locate water and able to withstand extreme temperatures, this upstanding, creeping plant occurs in woodlands and open plains in ephemeral swathes following heavy rains.

If you’re limited with time, there is a boardwalk from a roadside car park a little further north of the main entrance that leads to a platform with information boards and sweeping views over the garden. However unlike European gardens, the beauty of this garden is best experienced walking through it, taking in a more sum-of-many-parts detailed observation.

On the left is Eucalyptus kruseana or Book Leaf Mallee. It’s a distinctive straggly mallee only found in three hilly areas near Kalgoorlie, WA. The yellow flowers are in groups encircling the branch with its leaves closely spaced, round, green-grey and thick. On the right is Callitris glaucophylla or White Cypress Pine. It’s found across arid areas of inland southern Australia; its wood white ant resistant and used extensively in the past for fence posts. The bark was also used for tanning due to its high tannin content.

On the left is Eucalyptus youngiana or Ooldea Mallee. It’s found in the Great Victorian Desert from central South Australia to Kalgoorlie. The lid that covers the flower prior to fully opening gave May Gibbs the idea for the Gum Nut Baby stories. On the right another laser cut sculpture; a kangaroo in steel much preferred than the living version for whom the Garden is one giant banquet.

On the left are the cones of Allocasuarina helmsii or Helms Oak-bush. It’s found throughout South Australia and Western Australia on lower slopes of sand dunes. On the right, garden furniture that features in the AridSmart Display Gardens as part of the Highlights Walk where separate garden layouts have been created to demonstrate the beauty that can be achieved in a water-wise garden.

The other showcase location in Port Augusta worth a stay-over for is the Wadlata Outback Centre in which you can experience the ‘Tunnel of Time’ exhibition. Deceptively small on the outside, this self-guided tour takes you through the geology, Aboriginal Dreaming Stories, the stages of early European exploration and today’s experiences in the South Australian outback. You can whizz through it in under an hour or taking in the enormous amount of information on offer, plan a 4 – 5 hour visit.

From Port Augusta I traveled 190km along the very flat, open and often very windy Stuart Highway to Pimba and Woomera. Limitless skies, horizons that yield to the curvature of the earth, space, peace and the freedom to just be.

Woomera is an artificial town that was established in 1947 as a secret base for Anglo-Australia rocket and weapons testing. On arrival into what strangely feels a bit like an abandoned film set, the National Missile Park features predominately with a display of rare aircraft, rockets, bombs and missiles covering the full period of the Range’s operations.

In 1946 the Australian government received a formal request from Britain to establish a rocket range. The decision to build a rocket range was made in the postwar environment when the world was still recovering from the slaughter of World War 11. As a result of German rocket attacks on Britain during that war the British had decided they needed a rocket testing range and the isolation of Woomera combined with its proximity to the railway siding at Pimba made it an ideal location. Woomera also supported the Narrungar tracking station established under the joint defence program between the Australian and American governments. This facility closed in 2000.

During the 1960s Woomera’s population would fluctuate between 3,000 and 5,000 depending on the test programs but with the closing of the Narrungar facility it has reduced to a present level of about 140. Not open to the public until 1982; the Woomera Range Complex is still operated by the Royal Australian Air Force, a division of the Australian Defence Force.

With the public facility buildings of the 1960’s era, the absence of any visible recognition of the impact such a facility has had on the traditional owners and the emptiness of the streets, Woomera strangely feels like it’s stuck in a time capsule.

Another 126km up the road I stopped at Glendambo for the night. Officially constituted as a town in 1982, you’re now hard pushed to recognise such an existence. It’s only significant purpose to the public has been as a fuel and rest stop as the next refueling possibility traveling north is Coober Pedy, 254km away.

The hotel, motel rooms and caravan park have not been maintained and over the years have fallen into disrepair. There are two fuel stations, a Caltex and a BP; the later having some kind of agreement with the hotel for take-away food supply although it too seemed to be in a state of equal disrepair. The Caltex seemed better cared for and run with all bowsers functioning and a simple but fresh roast lamb and vegies on offer for the evening meal that night.

Admittedly the angle of the shot amplifies the somewhat sci-fi effect, but the only living thing that seemed to be thriving was this entangled gnarly cactus.

After refueling for the long stretch ahead, I continued north to Coober Pedy. There are several stops along the way that take in distant dry salt lakes and rocky open plains. This one being Lake Labyrinth.

I arrived in Coober Pedy late morning. The town takes its name from the Aboriginal words Kupa – meaning uninitiated man or white man and Piti – meaning burrow. The welcome sign at first seems a curiosity that makes no sense until time spent in this desert community reveals that this common modified vehicle is called a blower. Through local ingenuity they were developed in the late 1960s to suck the dirt and rocks up through large pipes into a hopper, which would periodically dump it on the ground into large pyramids of dirt. These mounds, called mullock heaps, as can just be seen on the horizon line of this photo, cover huge areas around Coober Pedy.

If you’re not prone to claustrophobia staying in a dug out is a unique experience that immerses you into the heart of life in Coober Pedy. It’s said that dugout living began in Coober Pedy when soldiers returned from the trenches of France in 1918. Although very basic in the beginning it was discovered how comfortable underground living could be given the ferocious 45˚C – 50˚C summer temperatures and icy 4˚C winter temperatures. The internal temperature stays between 18˚C – 26˚C year round and the cost is cheaper to build than an above ground home. Initially carved out with a pick or with the aid of explosives, modern dugouts are now excavated out with square and round tunneling machines. The town is now off-limits to mining although many ‘renovations’ of dugouts continue.

I stayed at the Lookout Cave Underground Motel located close to the central area of town. The rooms were well ventilated, modern, clean and comfortable. Along with experiencing a stay inside a sandstone hill, there was access to the top via stairs and a track from which 360˚ views, most spectacularly on sunrise and sunset, can be taken in. The above early morning shot is of the ‘roof’ of the motel with the air vents pocking through, looking north west.

After unpacking and settling in I headed out to pottle about and visited St Elijah Serbian Orthodox Church. Coober Pedy’s population, currently around 1,800, is surprisingly diverse with around 50 nationalities, including Serbian, Croatian and Greek communities. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people make up around 17% of the population. The hill that this church was tunneled out in was donated by a local man whose grandfather did the same in the former Yugoslavia after the war and wanted to continue a family tradition.

A feature of this church is the spectacular stained glass window. The window is though made of printed perspex as the summer temperatures would melt the lead used to hold traditional stained glass windows together. An unusual combination of traditional iconography and Sturt Desert Peas.

The digging of the church began in February 1993, and was finished in August 1993, with the work solely undertaken by volunteers. A road tunneling machine was used to start at ground level, digging out five 30 metre long drives into the sandstone to create the cinquefoil arch. The main body of the ark-shaped rectangular building was then tunneled out using a square machine, picks, shovels, jack picks, explosives and wheelbarrows. The floor is 17 metres under the ground level in the deepest point, and 3 metres under the ground level at the shallowest point.

By stark contrast to the church, the next morning I rode a few kilometres out of town to visit the now famous dugout of Crocodile Harry’s. A kind of temple-like cave filled with an eccentric collection of objects, women’s underwear, clothing, markings, tribal graffiti and messages from a crazy unfettered life.

It’s easy to see why Crocodile Harry’s nest was used as a set in the movies Pitch Black and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. His real name was Avid von Blumenthal. He claimed to be a baron from Latvia who fought for Germany in WWII after which he came to Australia where he hunted crocodiles for 13 years in the Northern Territory before coming to Coober Pedy in 1975.

Harry was a notorious personality in the town and well known for both his insane home and for his love of women. He died in 2006 but his legend continues to contribute to the town’s abundant stories of the many oddballs, misfits and escapees that have sought freedom from societal norms and conformity in Coober Pedy over the years.

In the afternoon I took a small group Town & Breakaways tour with Noble Tours. The first stop was The Umoona Opal Mine & Museum; an original opal mine on Coober Pedy’s main street that has been converted into the town’s largest single underground tourist attraction.

The tour guide took us through the original mine, explaining the harsh and rudimentary conditions the first miners worked in. Opal was first discovered by 14 year old Willie Hutchison, who in 1915 was camping with his father on an unsuccessful search for gold, north west of the Stuart Ranges. It’s had a boom and bust cycle through the years since. Opal mining has always been undertaken by individuals or small syndicates due to its fragile and sporadic, surface level geographical nature. It can’t be quantified through exploratory drilling. Opal mining is also covered under different laws to the bulk extraction mines in Australia.

From the town site, we headed out towards the Breakaways via the Moon Plain. This vast lunar-like landscape extends over 1,500 km2, 18 km north-northeast of Coober Pedy. The locality derives its name from the overall lack of vegetation and a flat hummocky landscape that resembles the surface of the moon.

Another stop was to take a look at the Dog Fence; a 5,300km unbroken barrier through South Australia, Queensland and New South Wales that prevents dingoes entering the sheep grazing country in the south. The South Australian section is 2,250km long. $25 million dollars has been allocated to replace and fortify 1,600 kilometres of the current fence line in South Australia, which has recently begun.

The Kanku-Breakaways Conservation Park covers almost 15,000 hectares featuring majestic arid scenery. Within the park are a series of flat top mountains that have broken away from the Stuart mountain range, hence their name. There are two lookout points which highlight the open spaces and colourful environment, leaving an impression of the long gone inland sea that the early explorers dreamt of.

On our return into town, our tour guide Aaron took us to one of the 80 opal fields 20km north of Coober Pedy where he has his own claim. In this section of the opal field there is a less common area of open cut mining.

Opals are multi-coloured and consist of small spheres of silica arranged in a regular pattern, with water between the spheres. The spheres diffract white light, breaking it up into the colours of the spectrum; this being called ‘opalescence’. These massive 80 metre long tunnels that run 20 – 30 metres deep are part of Aaron’s claim of which he’s owned for 3 years. Damp cool breezy air finding its way to the surface can be eerily felt when standing in front of these massive tunnels.

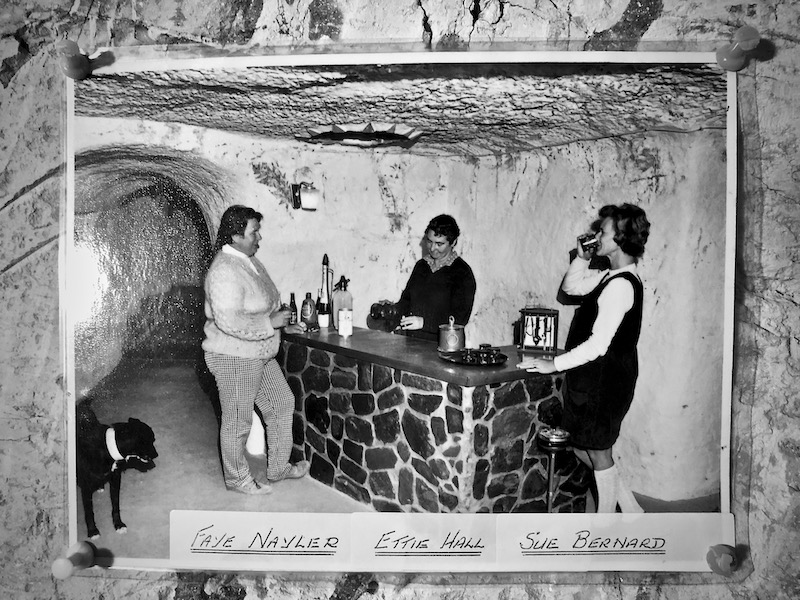

On my last day in Coober Pedy I visited the home of Faye Nayler. Now open to the public to learn about the life and work of another of Coober Pedy’s past iconic characters. Faye Naylor came to Coober Pedy in 1962 on a holiday and stayed. Together with her partner Sue Bernard they opened the Windlass Cafe, which was unfortunately demolished 12 months later by a tornado. Faye then began mining and dug an underground display showroom called the Opal Cave. She was the first woman to own and operate an opal mine in Coober Pedy, which also became a pioneering tourism business.

After completing the Opal Cave, Faye, Sue and friend Ettie Hall took 10 years to dig out their home by hand; mining for opals along the way. It remains fully furnished in a 1970’s style as if they’d just walked out the door. The main bedroom is 8 metres below ground. Along with her home being a central drop-off depot for all manner of freight and post, Faye loved parties and entertaining around her pride and joy, an internal underground pool and entertaining room.

There are so many stories of insanely crazy life and times in Coober Pedy, but the most visible on show in the main street is this door frame on a site that once was the entrance to a popular Greek restaurant. Up until relatively recently, dynamite could be purchased from the local supermarket and was the weapon of choice to settle disputes. A long running feud between a disgruntled local Hungarian man and the Greek restaurant owner some years ago resulted in the restaurant being blown sky high. Leaving the door frame standing alone pays a kind of hilarious, unhinged homage to this pride-of-place madness.

My final visit was to Josephine’s Gallery & Kangaroo Orphanage. The kangaroo orphanage came about 18 years ago as a need to care for injured kangaroos mostly hit by cars, or joeys from animals hunted for meat by local aborigines who are then brought into the orphanage. Being present during feeding time can be arranged by appointment and is popular with visiting families. The gallery is packed with aboriginal paintings, craft and opal jewellery.

A golden sun sets on another warm Spring 35˚C day and on my stay in this unique and isolated location in northern South Australia. I feel as if I’ve barely scratched the surface of this underground community that despite the famous lawlessness and frontier madness has a tight knit core of camaraderie, colour and richness beyond its opal heart.

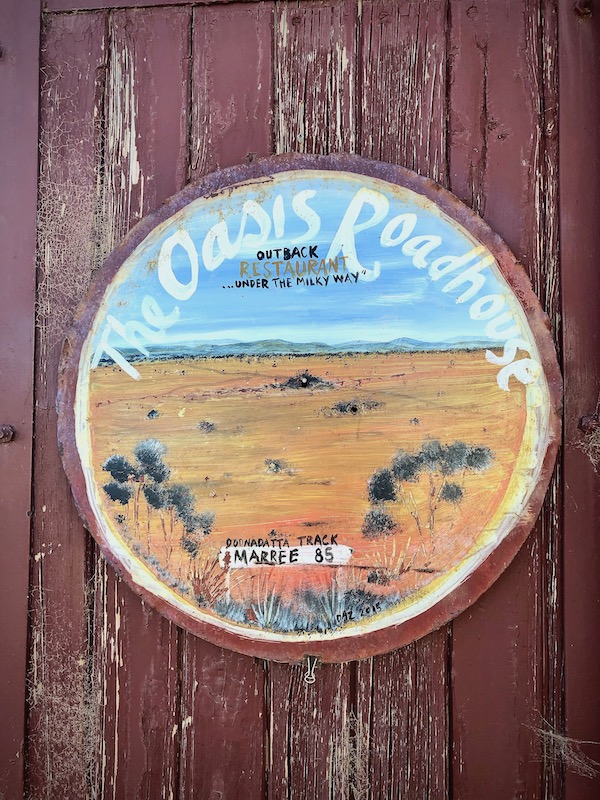

The following day I rode across to William Creek on one of the toughest stretches of unsealed roads so far. It took most of the morning to travel the deeply corrugated, multiple floodways, sandy and undulating 167km that passes into Anna Creek Station and onto the famous Oodnadatta Track; the entrance coming into William Creek feeling billiard-table flat and smooth.

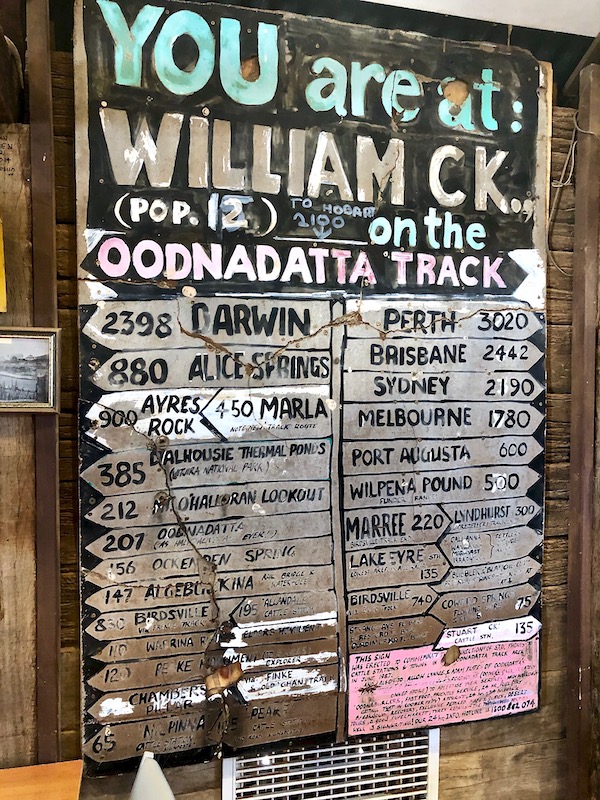

The iconic William Creek Hotel is the centre of this ‘town’, which is the closest settlement to Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre in Outback South Australia, on the Oodnadatta Track between Marree and Oodnadatta.

The Oodnadatta Track is an unsealed 617 km road from Maree in the south-east to Marla in the north-west via Oodnadatta. The track follows a traditional Aboriginal trading route and was also the route taken by the early explorer John Stuart on his third expedition in 1859.

Along the Track are numerous springs from the Great Artesian Basin, which provided water for the steam-train powered Ghan railway. William Creek is the central spot on the Track and remains of one of the railway sidings can still be seen along with the ever-present outback humour clearly on display in the pub.

With a tasty meal of goat curry, a night’s sleep and the essentials taken care of I left early from William Creek to head south, riding 204km along the Track to Maree.

The first stop along the way was at the oasis Coward Springs. An original bore has been restored and a natural spa created and maintained for public use nearby to a campground and permanent wetland. High in mineral salts and a constant 29˚C the spa makes for a relieving soak in an otherwise arid and dry environment.

The Engine Drivers Cabin is one of only two buildings along the Track that have been restored using traditional methods and to original plans. It is now a museum with displays of the unique history of this location and the local ecology.

The second stop along the way was at Lake Eyre South. It’s impossible to take in or capture the magnitude of this vast area, which is Australia’s largest salt lake. It’s made up of two lakes joined by a 15km channel. The Lake is the lowest point below sea level on mainland Australia and has been an important cultural site for Arabunna and other Aboriginal people for several thousand years. Lake Eyre South is believed to be the home of Kudimudra, a bunyip like creature in Aboriginal mythology who eats those who stray onto the lake. Aside from the ever present marauding flies, even more reason to respectfully depart.

I arrived in Maree, originally known as Hergott Springs in the early afternoon. Along with the roadhouse / general store, the Maree Hotel is the focal point in this historic town and where I stayed for the night.

Maree was a major rail-head for the old Ghan Railway named after the “Afghan” cameleers who transported goods by camel from Maree through Oodnadatta and onto Alice Springs and other areas. After miners and pastoralist’s successful demands were passed, work on a railway line from Port Augusta to Darwin began in 1878 reaching Maree in early 1884. The “Afghans” were generally Muslims from then-British India, although some came from Afghanistan and the Middle East. Three mosques existed in Maree, the earliest claimed to be the first mosque to be built in Australia. The above structure is a replica that was rebuilt in 2003 by descendants of the original families that still lived there.

Pieces of its railway past are dotted around the town as are remaining scattered pieces of this once vital historical settlement. Maree was a camp for the Overland Telegraph Line maintenance workers; an outpost for all early expeditions heading north; where the Birdsville Track and Oodnadatta Track were developed and the home of the mysterious giant geoglyph the ‘Maree Man’.

The following day I traveled a further 244km south to Arkaroola Village; a Wilderness Sanctuary located in the Northern Flinders Ranges and founded by the Sprigg family in 1968.

The road from Maree down to Copley, close to Leigh Creek and the halfway point to Arkaroola, has now been fully sealed. Prior to leaving the bitumen I refueled the bike and also my energy levels on a quandong pie from the Copley Bush Bakery & Quandong Cafe. Here pictured alongside the beautiful native Mulla Mulla that was flowering prolifically in patches.

Arkaroola features many unique geological monuments, rugged mountains, towering granite peaks, magnificent gorges and mysterious waterholes, the home to a huge range of species of birds, reptiles and mammals including the shy and endangered Yellow-Footed Rock-Wallaby.

The first morning of my 2 night stay was an insightful bush tucker walking tour with local indigenous Adnyamathanha man ‘Sharpie’.

Within a 3km radius of the Village, Sharpie identified many plants used for both culinary and medicinal purposes including this wattleseed. He explained that the women knew to harvest this seed when they observed a certain star configuration occurring in the sky they called the 7 sisters. Wattleseed was most commonly roasted, milled into a flour and used to bake a type of bush bread.

Quandongs were also ready to harvest, the above fruit located on a tree just outside the room I stayed in. Fossils from millions of years past are a frequent find, this slab of fossil-rich rock displayed on the entrance road along with other types of rock found in this ancient landscape.

Yam daisies also featured throughout the walk. The tuberous root of this plant was an important food source for Adnyamathanha people along with many other indigenous groups around Australia.

A major highlight of this entire trip and my visit to Arkaroola was the Ridgetop Tour. These 4 – 5 hour tours are run morning and night 7 days a week, starting from the Arkaroola Village, traveling to the highest point on top of Sillers Ridge. The above 4 wheel-drive vehicles carry 10 people each over extraordinarily challenging terrain along a hair-raising track that was originally laid by a mining company in the late 1960s to facilitate uranium exploration.

The drivers double as the tour guides who share their knowledge of Arkaroola’s 1,600 million year geological history. Inspiring vistas of red granite mountains and golden, Spinifex covered hillsides give way to breathtaking views across the Freeling Heights.

Sillers Lookout is the lofty pinnacle at the end of the track; the final narrow, off-camber, heart-in-your-mouth push towards a view that normally would only seem possible from an aircraft. This photo does no justice to the precariously steep and tight turn-around position these vehicles need to be expertly navigated on.

Razor-back ridges and peaks flood the breathtaking 360˚ vista that at its furthest point on a clear day, reaches Lake Frome.

An afternoon tea including ‘Arkaroola lamingtons’ is offered as you attempt to take in the stunning views over The Freeling Heights, a magnificent ring of saw toothed blue mountains that fringe the Mawson Plateau, the 1,000 metre deep Yudnamutana Gorge, salt lakes and the plains. A truly unforgettable experience and privilege.

The following day, a tail-wind made for an extra speedy trip interrupted by an emu emergency brake on a couple of occasions. My own feathers regathered and the slip-stream re-entered I’d well and truly built an appetite for lunch at the Prairie Hotel in Parachilna.

The Prairie Hotel was first licensed in 1876, the current stone hotel replaced the original structure in 1905. Fourth generation Flinders Ranges pastoralist and cattleman Ross Fargher and wife Jane, bought the hotel in 1991 and created a tourism brochure icon, famed for featuring feral and wild meat on the menu. The Thursday special that I chose for lunch was a ‘Sloppy Joey’ – barbecue pulled kangaroo, slaw and aioli on a charcoal brioche bun with chips. The Hotel also doubles as a gallery and shop for contemporary indigenous artworks from the eastern and western deserts of Australia.

Parachilna was originally a stop on the old rail line from Adelaide to Maree that then connected with the Ghan. The only business and substantial building in this once small outpost is the hotel. Situated close to the beautiful Parachilna Gorge, there was (and remains) in the early years a steady stream of traffic between the infant town and the nearby rapidly developing mining settlement of Blinman. The story goes that for a short time during 1869, camels were banned to pass through the narrow gorge as apparently horses did not see eye to eye with them and bolted when the camels approached. Horses won.

From Parachilna I continued on through the beautiful Parachilna Gorge to Blinman and then down to my final night stay at Rawnsley Park Station, located on the southern face of Wilpena Pound. It was settled as part of the Arkaba Station in 1851. Arkaba, Wilpena and Aroona were the first pastoral leases settled in the Central Flinders Ranges. Though tourism is the main industry on the property today, the Station still runs 2000 sheep.

There are several walks on small tracks and much longer hikes including packages, self-guided or hosted that can be taken from the Park. My efforts late on that storm-brewing afternoon amounted to not much more than a stroll, admiring the magnificent River Red Gums that feature prolifically in and along the waterways of this magical part of South Australia.

And here this journey ended. A quote on the entrance wall of the Tunnel of Time exhibition at the Wadlata Outback Centre in Port Augusta I saw at the beginning of this trip resonated: “Australia hides her secrets well; she buries them in myths and legends and stone”.

I look forward to uncovering more of what lays beneath and at the very heart of our extraordinary country again soon.