I realised not long ago that my Saturday morning obsessive ritual of driving 6km into town to pick up the weekend papers ahead of a double shift working day no longer grips me like some kind of substance withdrawal. It wasn’t so much that I was hanging out for world news, although the horoscope (desperate times…), restaurant and the arts reviews, favourite columnists, travel and human stories were / are pretty important; it was the security this fixed weekly routine offered during a difficult time that made the world feel a bit steadier.

The Coronavirus has certainly mucked about with these kinds of steadying routines and behaviours involving the world and people outside our homes. Also being a creature of habit, change isn’t always easy even if it’s the very thing I longed for most.

This period of being grounded in one place has really challenged my longed for wish of what I’d hoped being on the road would offer. Turns out though that no matter whether I’m moving from place to place or being in one spot for a while the things I love most can adapt and happen all the same. Particularly when the location I find myself in is rich with stories of place, people and food.

From a fresh and dried fruit grower in Angaston, hitting the local Barossa history and recipe books, foraging for mushrooms in the Mount Crawford Forest Reserve, a walk trail with rogue edible plants, places of historical significance revisited, an incredible veggie garden that’s part of a beloved Barossa wine institution, the Seppelts family mausoleum, a visit with my cousin who’s a baker in the Clare Valley, the beautiful Mount Lofty Botanic Garden and a visit to a Turkish family who are veggie growers in Murray Bridge that supply local restaurants and have a stall at the Barossa Farmers Farmers Market; these are some of the stories and food that May served up here in the Barossa Valley, South Australia and a little further afield.

In traveling through the Barossa today you wouldn’t know that there was once a thriving industry of fresh fruit growing and preserving other than the wine grape. So on a stunning Autumn day in early May I visited Gully Gardens. One of the last family owned and operated small orchards with a farm shop open to the public located on a beautiful 32 acre undulating property just out of Angaston. Despite financial odds and drought, Rick and Rosemary Steicke have continued to cultivate and grow several varieties of apples including the Cleopatra, which was a sturdy flavoursome variety shipped from the Barossa to the UK in the late 1800’s; apricots, pears, peaches, nectarines, plums, red and white Frontignan grape vines.

Rustic, beautiful years-old solid wooden cases and trays are still used for harvesting and drying. The fruit travels directly from the tree to their shop, the local farmers market for retail sales on a Saturday morning or to the processing shed for cutting, drying, confectionery making and packing just metres away.

Being a small operator that sells directly with very little handling and transport, varieties that have either fallen from favour due to fashion or damage issues have not been sacrificed. Apple varieties include: Cleopatra, Golden Delicious, Jonathon, Democrat, Fuiji, Granny Smith and Pink Lady.

In 2012, Rick and Rosemary made a sizeable investment in upgrading their processing and handling facilities after which they’ve since been able to continue their fruit growing and processing enterprise without the need for a second income. Sales are through their website, the local Barossa Farmers Market and their Gully Gardens Farm Shop. Along with the shop, there are a few curious farm animals always up for a feed.

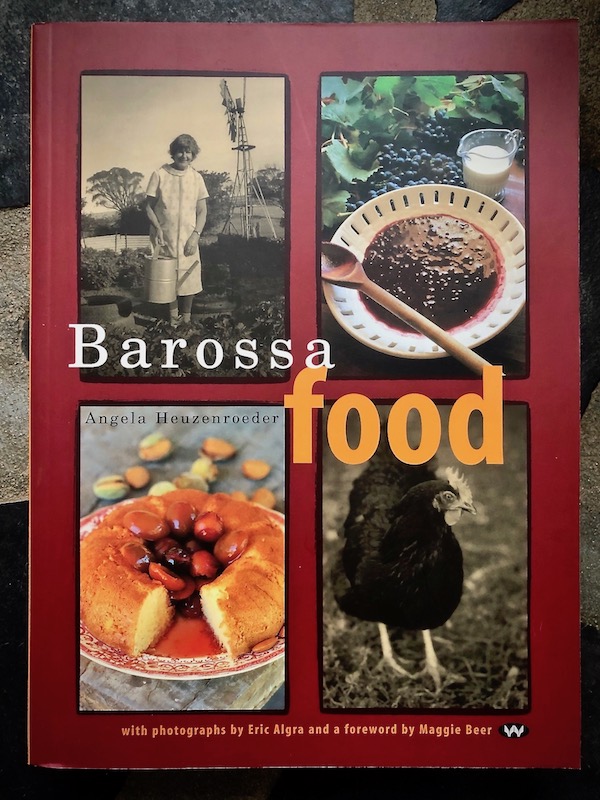

After coming away from Gully Gardens with bags of beautiful dried fruit and reading about the history of fruit in the Valley, I couldn’t resist making this simple pudding, which was based on a traditional recipe from ‘Barossa Food’ by Angela Heuzenroeder; ‘Backobst with a Champagne Crust’. In the early German Lutheran settlement years, dried fruit (backobst is the German translation) looked a little less appealing than it does today with the apricots more black than deep orange and pears more dark brown than golden yellow in colour. I’ve posted this slightly adapted recipe in the Baking Sweet section of this blog or the original can be found on page 213 of ‘Barossa Food’.

Along with bush walkers, campers, horse riders and mountain bikers the Mount Crawford Forest Reserve has long been a magnet for mushroom foragers. It’s located about an hour from Adelaide and 7km from the town of Williamstown, just outside the Barossa Valley. Despite the uniformity, there’s something that’s both wild and peaceful about being in a pine forest. The space between the thick soft carpeted forest floor below and the gently swishing tree canopy high above is like a vacuum for sound, smell and temperature that has a quietly cocooning effect.

Despite not finding the pine mushrooms, slippery jacks were easier to spot. Timing it seems is critical and Slippery Jacks are no poor second choice. The Mount Crawford Cemetery, which is located on a rise on the edge of the forest reserve was established in 1845 and is still currently being used as a public cemetery. Alongside the cemetery is the stone ruin of the Murray Vale Presbyterian Church which was built in 1843 and destroyed by bush fire in 1869. As a friend quipped, it’s a place that pushes up mushrooms along with daisies.

There are many bush walks and walking trails in the Valley. The one I have nearest and easiest access to is the 7km Angaston to Nuriootpa rail trail that follows the old rail easement featuring high embankments with views over the Valley and through the foothills.

Feral olive trees, the origins of which date back to the 1880’s litter the trail with vigorous resilience along with the mighty grape vine that during the month of May burn brightly with Autumn colour.

A cultivated olive grove has a sure footing on sloped rocky ground as the trail winds its way through cuttings quarried through the hill down to the Valley floor.

Along with native species, rogue introduced species of once cultivated plants can be seen along the walk such as rosehips on long forgotten rose bushes and gnarly prickly pears.

The weed fat hen, also known as lambs quarters, goosefoot and blue weed is prolific. It’s in the goosefoot plant family, along with spinach, beets, purslane and quinoa to which it is quite closely related and very edible. This lawn-mowing sheep however has its sights firmly set on the soursobs, which with recent rain has carpeted the Valley. Funnily enough, the common soursob is also known as wood sorrel and is sometimes used as a garnish in up-market restaurants. The taste, as many wild weeds have is subjective but it certainly sounds more eloquent on a menu than soursob.

Looking a bit bedraggled but nonetheless survivors, wild almond trees, fennel and dill can also be found through the Valley care of early settlers. Roadside fresh and dried dill is still used to add flavour between the grape vine leaves in the traditional Barossa pickled cucumber ferments.

The Angaston end of the trail has been cut through significant rock in which I spotted a two small stones with a written plea nestled on small ledges. A wonder how long these stones had been sitting in this strategic position and if the intended recipient Sienna saw this too. Perhaps given they’re still there, maybe not. As mobile phones are virtually glued to our palms, it seemed a curiously creative way to communicate a message from someone I assume is young.

Cemeteries are odd places to hang out but here in the Valley there are quite a few small ones with very old headstones written in German that tell a story of migration, dedication and sad loss; particularly of children. The Bethany Pioneer Cemetery in Bethany, which was established in 1842 is one of the oldest in the area that has a large gum tree now backed by vineyards that was said to have been used as a place of worship prior to a thatched roof church being built in 1845.

Bethany was the first village established in the Barossa Valley, which was laid out in the German Hufendorf style. Houses were built along the main road with their farmland stretching out at right angles in long narrow strips with access to water from the Tanunda creek. Community life was centred around the church and school. The current church was constructed during 1882 and characteristically literally named Die Herberge Christi zu Bethanien (The Dwelling place of Christ at Bethany). Behind the church are stone and split log post and rail enclosures that were part of a Barossa Vintage Festival event called Step Back in Time, showcasing heritage farm equipment and homemaking skills such as butter churning and traditional Barossan recipes. Throughout the rest of the year, visitors can learn about the history of this unique village by following the Bethany Heritage Trail, which highlights 22 locations of interest along a 5km return walk.

I have a vague memory of a school excursion to Hoffnungsthal. I couldn’t understand why we had to endure what seemed like a never ending bus trip on a cold wet day to see an empty paddock. Meaning Valley of Hope it’s a low lying area where an early German pioneer settlement was established in 1847 just outside today’s town of Lyndoch. Local Peramangk people warned the settlers that the area was prone to flooding, but this advice was ignored and after heavy rain in October 1853, the settlement returned to being a lagoon and the village was flooded. Eventually the settlers left to start again in Bethany and further afield. All that remains are the foundations of the church with a commemorative plaque honouring those buried in the now unmarked cemetery, a lovely view and a fated story of lost hope. On a beautiful Sunday afternoon sitting in the grass looking over this grassy depression in the land a few decades later I’m unsure if this story of willful ignorance and struggle was the actual intent of the school excursion at the time.

Angela Heuzenroeder’s wonderful book ‘Barossa Food’, first published by Wakefield Press in 1999 is a collection of recipes, stories and research of the culinary heritage of the German Lutheran settlers of the Barossa Valley. This incredibly tight-knit self-sufficient faith community in search of religious freedom and a better life was greatly supported in the very early years by George Fife Angas; who was an English businessman and banker that contributed largely in establishing South Australia. In hitting the history books in the local library, it seems he held strong principled views for the right to be able to practice a faith no matter the religion and as an astute businessman also knew the industrious hard working nature of this community would have greater prospects at succeeding in settling and growing the new colony. He was right and the legacy of this community’s food and wine culture, albeit with much adaption and some loss over 150 years of history remains today in the older wineries, bakeries, butchers, food stores and farmers market.

Rockford is a winery solidly rooted in the soil, stewardship and story of traditional craft wine making in the Barossa Valley. It’s a wine brand widely beloved in Australia and one, now I’m a bit of an old-boiler, also gravitate back to when the flood of choice, energy and noise of modern wine labels gets a bit overwhelming. Founder and wine maker Robert O’Callaghan purchased an 1850’s stone settler’s cottage and outbuildings on five acres of land in Krondorf in 1971. The courtyard shaped cellar door winery which grew from this was built in the same style and from the same materials as the original buildings and opened in 1984.

Robert O’Callaghan’s strong independent style and stewardship of the history of the Valley is very much the foundation upon which Rockford is built. Many years ago together with gifted chefs Michael and Alison Voumard, he invested in a large productive vegetable garden nearby to the winery that started and continues to supply two weekly lunches for the Stone Wallers. A group of friends and loyal Rockford customers that are treated to a Rockford wine matched lunch served in a private dining room at the winery.

Experienced chefs Sandor Palmai and his partner Lauren Remkes have now together with a small team of gardeners undertaken the care and management of the garden along with the cooking of the Stone Wallers lunches. I spent a couple of hours with Sandor on a beautiful Autumn morning who generously took me through the 3 acre garden and orchard that have become an expansion of the original German Hufendorf style and explained how the plant selection, planning and timing have evolved. Unique varieties of uncommon vegetables, ancient old fruit trees still bearing, ducks and chickens to assist with pest management

The property was originally settled by Johann Henschke prior to his move to Keyneton to establish Henschke Wines. A small original stone dwelling remains on the side of the hill comfortably nestled in the layout of this extraordinary garden.

Salsify is an uncommon and unassuming root vegetable that is sometimes also called oyster plant as it said to have a mild oyster-like taste. Other flavour descriptions that speak a little stronger to me are of artichoke with a trace of liquorice. Either way it’s delicious, rare and to see a whole row of it in unbelievably flourishing health was an absolute treat along with watching handsome Herr rooster on faithful guard of his flock of Australorp girls under the fruit trees.

The Old Union Chapel in Penrice, an area along with Angaston originally called German Pass, is one of the oldest churches in South Australia and Angaston’s first public building. With then seating for up to 150 people and open for all denominations, the land and money to build it was donated by George Fife Angas. It opened in February 1844 and used as a chapel for 10 years until a larger union church was built in Angaston. The building was subsequently used to store fruit, was a private residence and shearing shed until the Angaston Council bought it in 1989 and took on restorations for its 150th anniversary. It’s now again available to the community for public and private events.

I’ve always been a huge fan of oatcakes. When choosing some kind of dried biscuit or cracker for the provisions I carry on my bike it’s always been a time and effort toss up between bought Finn Crisp rye sourdough crackers or home-baked oatcakes. On a recent wet day I pulled out the recipe after which several were quickly topped with a smear of quince paste from the slab drying next to the heater, some fruity Adel blue from La Vera Cheese and a sprinkling of crushed fennel seed. An instant reminder of food’s magical restorative power. Another comforting restorative power of well-being over the years has been the gentle rhythm of knitting needles. Being a very basic knitter, knitting projects have remained as simple as they come and knitting napkins has been one of the lovely legacies of having been married into a Swiss family. My versions are of course much chunkier and ‘rustic’ by comparison with the fine Swiss cotton originals of my past mother-in-laws’ but I think of her and the meals at her table set with her beautiful napkins as my needles clumsily clack away into the cold nights.

Another local place of historical significance visited on a school trip was the Seppelt Family Mausoleum in Seppeltsfield; the private burial ground of the Seppelt Family. The family built this mausoleum to the memory of Benno Seppelt, the son of Joseph Ernst Seppelt who left his tobacco, snuff and liqueur factory with his wife Johanna, children, factory workers and 13 other local families from Lower Silesia (now Poland) to travel to South Australia in 1849. Although not evident in the above photo it’s a good hamstring workout walk up the hill to the Doric-style vault from which the living and the dead enjoy beautiful sweeping views across Seppeltsfield.

Seppeltsfield is characterised by its 2000 Canary Island Date Palm lined road that were planted during the Great Depression in the 1930’s. The Seppelt family were renowned for their strong bond with their employees and the wider community and during this difficult time planting the trees kept the employees in work while production from the winery had greatly reduced. The Mausoleum and palm trees remain a personal and public legacy of the generosity, care, hardworking, enterprising and philanthropic nature of this early Barossa pioneering family whose contribution to the Valley and the early years of the wine industry in Australia was significant.

Bread is ancient. Taking many forms it’s a universal staple that tells the longest story of culture and location like no other food. It’s both simple and complex, science and art and a long love of mine. My cousin Chris Harris and his wife Amanda who own and operate Clare Rise Bakery in Clare, South Australia are also dedicated to the pursuit of bread happiness. Chris’s above ciabatta came first in last year’s Royal Adelaide Show Professional Baking section. It’s easy to see and taste why.

On a Friday night, his 6th working night of the week, Chris’s shift starts around 10 pm and finishes around 7am. As Saturday’s trading is a shorter day he normally bakes alone producing a wide selection of breads, savoury and sweet buns, donuts, pastries and pies that are sought after by locals and travelers passing through the Clare Valley.

Chris and Amanda have a diverse wholesale and retail customer base that have varied tastes. In catering for the more artisanal-interested, his delicious sprouted wheat sourdough offers a free-form, deeper more developed flavour and crust.

An interesting bit of information Chris shared was that the reason the sandwich-style square loaves are formed with 4 pieces of dough that bake together to make one loaf is that this contributes to the loaf staying fresher for longer. The knowledge and skill of bakers is like many trades sadly replaced by large scale industrial and imported product. Together with the hours and physical toll it’s easy to understand why bakers like cooks retire from the industry at a relatively young age. Chris and Amanda too feel this demanding strain and have put Clare Rise Bakery on the market with the hope it can continue as successfully as they’ve grown it to be and they can again enjoy life with a healthier body-clock schedule and time to travel again.

The Adelaide Hills is a region well-known for it’s European-like feel with small towns positioned near to each other, white-knuckle windy roads and beautiful gardens especially in Autumn and Spring. Covid kept the Mount Lofty Botanic Garden closed for several weeks over most of this stunning Autumn season but with a couple of friends, we braved the crowds with as much social distancing strategy as possible when it reopened a couple of weeks ago to enjoy the last this leafy botanical kaleidoscope of colours and shapes.

The 97 hectare garden opened to the public in 1977 but started out as a proposal in 1911. There are walking trails of varying difficulty that also includes The Nature Trail, which offers a glimpse of the native flora that would’ve dominated the region prior to European settlement. The Lakeside Trail is a more domicile formal affair, offering a range of sculptures with important environmental messages.

Set in the historic Yalumba Vintners Shed just out of Angaston, the Barossa Farmers Market has traded nearly every Saturday morning since 2002. With controlled, zero contact measures and a new online ordering system in place, it recently reopened after restrictions halted trading for a few weeks. Browse buying has also just resumed, which now also allows for conversation with stall holders, which is as much of a market experience as the fresh produce purchasing. I got chatting with vegetable grower Kasim Erkoc who has a stall with a variety of vegetables both common and uncommon and also worked many years as a chef, growing vegetables for his own restaurant in Adelaide for a time. He invited me to come to his farm in Murray Bridge to take a look at what he and his family grow. So on a recent sunny Friday morning I rode across to visit them.

When I arrived Kasim and his wife Reyhan were pulling and bunching carrots for the market the following morning. They grow an astounding number of different vegetables over fields and in glasshouses for many of the Barossa and Adelaide high end restaurants along with the weekly farmers market. Kasim was born in Melbourne but his parents migrated from Turkey and Reyhan was born in Turkey. Kasim tells the story of how he ended up in Murray Bridge. On a very rare family holiday his family’s car broke down in Murray Bridge, which forced them to stay for a couple of days. His mother had long suffered from headaches but while waiting for the repairs to be done they disappeared which initiated the family’s relocation. With a background in market gardening, the family reestablished themselves over a number of years and have been growing beautiful vegetables with enormous care and dedication in the rich Murraylands soil ever since.

The family’s glasshouses are many years old. Despite their constant repair, Kasim prefers to grow in soil under glass than poly tunnels and when others in the area are no longer used, he seeks them out to ensure his stockpile of glass replacements are maintained.

Popular in Holland and Germany, in central Europe and in Israel, China and India, kohlrabi has only recently become known here but is now a regular offering at his market stall that sits alongside with the ever popular and pretty purple, white and orange coloured carrots.

Going through the expensive and arduous quarantine process to import seeds, Kasim and his family brought a special variety of tomato they knew and loved in Turkey to Australia. As they’re not a hybrid variety and remain true to type, he can save the seed from year to year to again propagate and successful grow to yield delicious tasting tomatoes.

I’m not too sure what this coming month will bring but as we’re adjusting and adapting to the unpredictability of the world our basic needs remain a constant. Whichever way we’re headed I hope those needs provide pleasurable purpose and in between there’s a quiet space for wintering rest and awe for this incredibly beautiful ancient country we’re all so privileged to live in.

A quote from the back cover of Julia Baird’s recently published book Phosphorescence is a soft guiding light for what can sometimes feel like dark times: ‘How do we continue to glow when the lights turn out? All we can do really is keep placing one foot on the earth, then the other, to seek out ancient paths and forests, certain in the knowledge that others have endured before us. We must love. And we must look outwards and upwards at all times, caring for others, seeking wonder and stalking awe, every day, to find the magic that will sustain us and fuel the light within – our own phosphorescence.’

Until next time.