From January into February the weeks have passed with a slideshow of ever changing landscapes, temperature contrasts and memory-making experiences. From the border I rode through the Eyre Peninsula to the Flinders Ranges, down to my home-patch of origin the Barossa Valley, across to Kangaroo Island and back to the Barossa in time for the beginning of vintage.

Traveling along the west coast of the Eyre Peninsula from Ceduna to Coffin Bay with a coffee stop in Streaky Bay revealed rocky, wind swept frontier landscapes with crumbling stonewall remains of early brave South Australian settler homes that you commonly see littered across the state.

Having visited Coffin Bay in peak winter oyster season a couple of years ago, expectations of cold-induced fat, creamy fresh oysters full of salty sweet briny juices of the winter sea in the off-season month of February were pretty low however were met with not too shabby an offering.

Taking a tour with Pure Coffin Bay Oysters out to the oyster beds on a sunny winter’s morning in 2017 was magical. Row after row of submerged oyster filled baskets at varying stages of growth need constant management. Growth rates and harvesting according to market size-demand vary which are regularly sorted, checked, repacked and re-submerged. Tasting and learning about the differences between the market-common Pacific Oysters and wild native Angasi Oyster was a revelation and delicious memory on an unbelievably gorgeous morning.

Coffin Bay is a town made up of a small permanent community and large fluctuating seasonal tourism population. Beach houses filled with generational histories of family holidays line the coast around the bay. I was fortunate to stay a couple of nights at a friend’s ‘The Green Bottle’ shack that was located close by to The Oyster Walk.

The Oyster Walk is a 10 km walking trail that follows the foreshore along the town of Coffin Bay. At the eastern end (the Port Lincoln end) there is a loop to a lookout in Kellidie Conservation Park, and an out-and-back trail to Old Oyster Town in Kellidie Conservation Park.

Old Oyster Town dates from the mid-1840s when Europeans first started harvested local wild oysters. After 1882 the fishery faced periods of official closure due to over fishing, and the native oysters never recovered. There is little evidence now of Old Oyster Town, except for some wells and a very large rosemary bush (over 30m across) dating from 1850.

From Coffin Bay it was on to Port Augusta and then in to the ancient Ikara-Flinders Ranges National Park. The park is approximately 95,000 hectares and includes the Heysen Range, Brachina and Bunyeroo gorges and the vast amphitheatre of mountains that is Wilpena Pound. This view is from Huck’s Lookout. One of the many vantage points between Wilpena and the tiny township of Blinman.

Mining and the history and development of South Australia are closely connected; particularly in relation to the development of townships in the Flinders Ranges; Blinman being one of these towns. It is officially the highest in terms of meters above sea level. In its heyday in the 1880s, at the peak of copper production, Blinman had a population of 1,500. Now there are only 18 permanent residents. The underground mine tour experience offers a unique journey into the heart of an historic copper mine that uses storytelling, light boxes, music, a mix of theatre and mining history facilitated by a terrific tour guide, transporting people back in time to the lives of the miners and their families.

The formation of the Flinders Ranges began about 800 million years ago. An ancient sea which covered the area for about 300 million years depositing sediment over the area. The Ediacara Hills in the northern Flinders Ranges is the site of discovery of some of the oldest fossil evidence of animal life. The Flinders mountains are described as a classic example of a folded mountain range, which is when two continental plates collide.

The Great Wall of China is another interesting geological feature just outside the park that was named so due to its resemblance to the original. Inside the park I took the 7km return Wangara Lookout walk along the Wilpena Creek through the gap leading into Wilpena Pound and the Hills Homestead.

When the Hill family obtained the lease for the Pound in 1901, they decided to try farming, something never before attempted so far north. After the immense labour of constructing a road through the Wilpena Gap, they built this small homestead inside the Pound and cleared some open patches of thick vegetation in the interior. For several years the Hill family had moderate success growing crops, but in 1914 there was a major flood and the road through the gorge was destroyed. They could not bear to start all over and sold their homestead to the government. Renovated from ruin in 1995 by a local craftsman, the crumbling walls, rotting beams and collapsed verandah of the Hills Homestead were restored, bringing it back to its original glory.

There are a variety of accommodation options on offer at the Wilpena Pound Resort, including powered and unpowered camping sites. Camping is as enjoyable as the comfort of your gear allows and my Mont tent made for a brilliant sturdy nesting spot for a few nights.

On to the Barossa Valley. The history of the Barossa dates back to the early 1830’s when it was first named after Barossa of Spain, by the then Surveyor General of South Australia, Colonel William Light. But it wasn’t until 1842 when both English and German settlers first came to make their mark on the countryside of the Barossa Valley with early plantings of vineyards and orchards. Owned by Orlando, this showcase vineyard called Steingarten was established in 1962 and is located on the steep east facing rocky outcrop in the Western Barossa Ranges.

My life in food began with Maggie and Colin Beer at the end of 1984 at the then Pheasant Farm Restaurant. The site today is very different to the early days of a small regional a la carte restaurant offering a variety of dishes based around the game birds that were farmed on the property. Ahead of her time, Maggie cooked instinctively and in tune with the availability of seasonal produce in a style that was provincial and set a high bench mark for Australian regional dining experiences. Today it’s an international culinary tourism icon that visitors around the globe seek out. For me, it’s like coming back to what now, some 30 years later feels like a long ago dream that I feel enormously privileged to have been a part of.

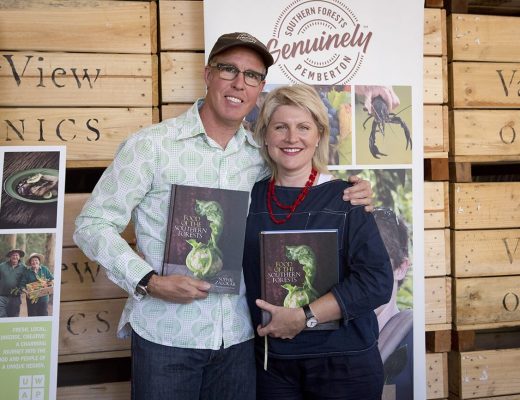

This photo was taken after a tribute dinner for Maggie as part of Tasting Australia in 2017. Together with other early-day chefs, we cooked a course each that told a story through food of our connection to Maggie and this iconic period of Australian gastronomy.

The Pheasant Farm Shop now offers a wide range of Maggie Beer products and tasting experiences along with cooking demonstrations of how to use these products in delicious recipes.

Rockford Wines is another iconic Barossa experience that speaks of provenance and an authentic traditional Barossa wine story. A visit here brought back memories of the very first Barossa Gourmet Weekend in 1985, serving hundreds of plates laden with confit duck leg, pickled quince, tarragon bread and salad greens.

Kangaroo Island, much like Rottnest Island for West Australians, is South Australia’s holiday isle home away from home. 15km from the mainland and accessed by ferry or plane, it’s surprisingly larger in size than expected. From east to west it’s 150km long and 57km at it’s widest point. The coastal town of American River has the only commercial oyster farm on the island with a retail outlet offering both oysters and local seafood. Along with a lunch of fresh oysters and pan-fried garfish, I purchased their in-house smoked mullet for a simple holiday kedgeree. A dish of Indian British history based on curry, rice, eggs and smoked fish. I also added peas, bean sprouts, lime and lots of fresh coriander.

As the weather was not going to be great for camping, this simple ‘Fishermans Hut’ on the beach in Brownlow, Kingscote was a charming little base with simple cooking facilities.

Kangaroo Island is home to the last remaining pure stock of the docile Ligurian honey bee in the world. The island was declared a bee sanctuary in 1885 with no other bees imported on to the island. Recent devastating fires destroyed up to a quarter of the islands hives and much of the unique habitat that produces the honey’s unique flavour. Taking a 20 minute tour of the Island Beehive facility in Kingscote was an interesting inside into the complex and highly organised world of bees and relieving to know that not all has been lost of this incredibly special honey production.

A ride around the island was incredibly sobering. Kilometer after kilometer of blackened annihilated landscape with an empty eeriness devoid of life except for a hopeful shoots sprouting from the bases and limbs of some trees.

The charred remains of bark from thousands of trees had cracked in chunks and fallen to the ground like an exoskeleton revealing exposed and denuded limbs.

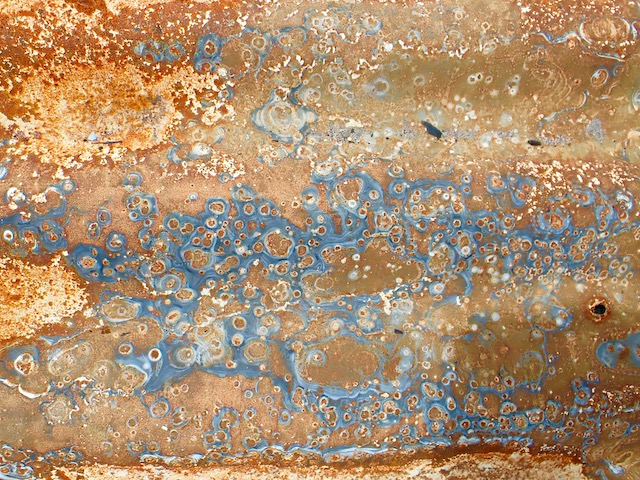

Sheets of rusted corrugated iron exposed to ferocious temperatures resulted in marbled patterns of melted metal and mineral. One of the locals I spoke with said that temperatures of close to 400 c had been recorded and the speed at which the majority of the severe damage in the Chase National Park on the Western end of the island that occurred took as little as 4 hours…

Returning to the Barossa I spent a day tagging along with an old friend who manages many vineyards around the Valley. Due to a variety of climatic reasons the 2020 vintage has shaped up to be one of the lightest in terms of crop volume and fruit quality on record. The point at which harvesting begins is a decision driven by the winemakers in discussion with grower liaison officers and the vineyard manager.

Looking like some kind of giant insect with a value close to the cost of an average 3 bedroom house in a sought after suburb in an Australian capital city, this modern grape harvester makes quick, clean and light work of the vineyard very unlike the early mechanical harvesters that I remember from many years ago.

At an average speed of 5km per hour during the cooler periods of the day and night, cupped ‘fingers’ and belts lift the individual grape berries off the stalks and deposit them in an onboard holding tank, which then is tipped into bins that are taken to the winery.

Hand picking has not been made altogether redundant as winemakers will still request this over mechanical harvesting for some of the varieties and highly valued vineyards.

Once the bins have been delivered to the winery the fruit is then tipped in to tanks for the wine making process after which can then be stored in oak barrels for maturation and blending.

Book-ending this post, a crumbling stone wall of beautiful colour and texture in a dry field feels like an apt way to conclude my time in South Australia for now. Rich with a history of great tenacity, tradition alongside innovative social, cultural and artistic endeavor this state of festivals and Adelaide being the city of churches will always be the state I return to with a sense of familiarity and belonging.